BACK FROM THE DEAD: A Cautionary Tale from the Uwharrie 100

DEDICATED TO JTD

0.0

It was fucking impossible. There’s no way my brother was still in this race. I must have been hallucinating again - after all, it was mile 99 and I saw everything from my 4th grade teacher (she’s dead) to my uncle dressed as Santa Claus (his suit was pristine). The last time I saw my brother – over 10 hours ago, at mile 70 - he moved like a sedated Dr. House: cane, obscenities and all. Yes, it’s true that John is a freak athlete. Yes, it’s also true that he’s completed 100-mile races before. But John was 8 weeks out of IT Band surgery; the PT had just cleared him for “brisk walks.” He had collectively trained 12 miles prior to the Uwharrie 100. More specifically, John ran 12 miles on the Monday before the race. That’s right, a 12 MILE TRAIN UP on a surgically suspect leg for one of the most brutal 100 milers in the country. John was supposed to be part of my crew, for god sakes, until some satanic impulse compelled him to tell me seven days out, “I’m in.” As someone who doesn’t know John, I don’t blame you for asking the question, “why?” – we’ll get to that – but for right now, I want to set the stage for “how.” At mile 70, if you gave me odds on an actual Sasquatch embracing me at mile 99 or my brother finishing in under 36 hours, I would have bet the house on a warm, furry bear-hug from Bigfoot.

1.0

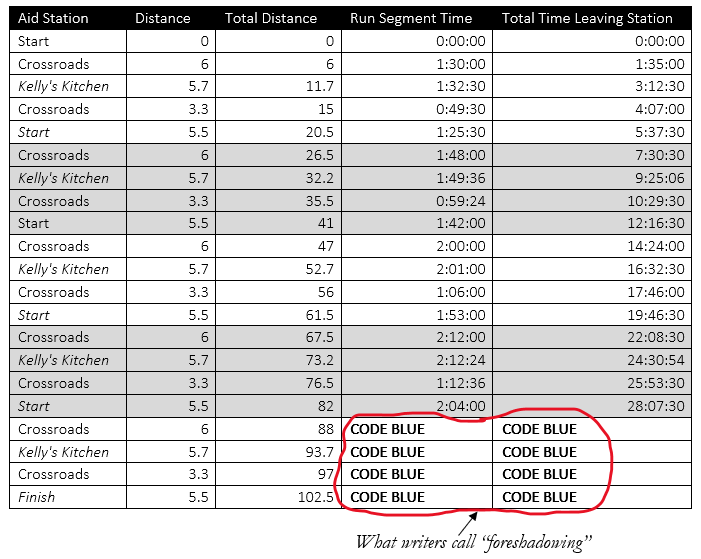

If you look closely enough, the math of an ultramarathon can tell a compelling, even terrifying narrative. The Uwharrie 100 was no different. Let’s start at the beginning: the plan for John and I (overtrained in comparison, with 6 weeks of total train up time) was to mirror previous race finishers in the 35–36 hour time frame. Although we had never attended a training run at Uwharrie, all reports about the course were 1) the terrain was incredibly unforgiving and 2) the elevation gain made completing the race in under 36 hours either a high-wire act or suicide mission, based on our training mileage. Undeterred, John developed a plan of attack:

The key number to hit, based on historical data, was 20 hrs and 30 mins at the start of the fourth loop. Anything above 20:30:00 gave us an infinitesimal chance of making the 5th loop cutoff of 29 hours. Unfortunately, the enormity of the task at hand was immediately evident after completing our first loop:

On paper, we were only about 12 mins behind schedule but the “race had officially started.” To be clear, the actual moment a race starts is not at the predesignated start time. You’ve probably seen it before: it’s the beginning of a race, the atmosphere is jubilant and people are overflowing with naïve, unbridled – and untested - joy. On the contrary, you’ll know the moment your race starts when the gravity of what it’s going to take to complete the race abruptly smashes into the painful reality of how little you have left. You can see it immediately in a runner’s eyes, it’s known as “The Look.”

The Look is best described as the physical manifestation of a runner’s soul attempting to leave its human host. At this moment, the runner is faced with the proverbial fork in the road: on the left, there is a beautifully lit path that is filled with comforting voices that say something like: “You’ve done what you came to do”, “I’m so proud of you”, “You could hurt yourself if you push on.” Probably the same bullshit that people put on their social media pages immediately after a race.

And then the runner looks to the right. There is no fucking path. Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata is playing in the background. Lightning strikes the gnarled earth with such force that you can only assume Zeus is pissed off. A rusted, dulled shovel is embedded in the ground like a demented Sword in the Stone and is daring you to grab it. It’s up to you to remove the shovel and create the path yourself – even if that means you might end up as a bloody mess, digging ass-naked through a briar-filled hellhole. Of course, there are no guarantees that you will even make it out. But, rest assured, it is the only way to maintain sovereignty over your soul. You see, those nice voices you heard on the “easy” path are actually Sirens of Comfort- charlatans who know exactly how to manipulate your every mental weakness. They might seem friendly, but if you let them, they will take everything from you. And so, at mile 20, in a 100-mile race, John and I picked up our shovels. It was time to dig.

2.0

We knew that once loop 2 (mile 41) was completed, another crucial decision had to be made. Do we inject our only pacer, Pat – who hit his lifetime mileage high of 6 miles the week prior – to give us a much-needed jolt or hold him back until later in the race? Originally, our plan was to reserve Pat until loop 3 (mile 60) for a 10 mile stretch. Employing him at mile 40 would be a “break the glass in case of an emergency” scenario and indicate our race had turned into a dumpster fire. Correction. A dumpster fire in the middle of an active volcano. As we slogged to the 41-mile aid station, John and I looked at each other. Change of plans. We need Pat. NOW.

The start of loop 3 marked nightfall and the tenuous grasp we had on maintaining our pre-planned race pace was slipping faster than a misstep on the backside of Soul Crusher Mountain. People often ask, “what does it feel like to run a 100-mile race?” Loop 3 epitomized the ultra-marathon pain sensation for me: it’s like sticking your finger in a door hinge and slamming it repeatedly for 25+ hours. It’s not enough pain to cripple you, but it’s goddamn annoying, and when you realize you’re the one slamming the door on yourself, it’s extremely tempting to just...stop.

Unfortunately, John and I never had the luxury of time to stop slamming the door on ourselves. We were Clydesdales being prodded by our dutiful coachman, Pat. Any lack of discipline on John’s or my part would mean an eventual time out or the worst reality imaginable: being forced to run an unfathomable negative split (running faster than our 3rd loop) on loops 4 and 5, to stay in the race. To put a negative split in perspective, Matthew Estes - who holds the Uwharrie 100-mile course record with a 20:27:04 (a feat of human achievement so great that it demands his likeness be carved into a rock atop Hallucination Hill) - did not run negative splits after loop 3. Needless to say, the future of our race looked as bleak as the Western Carolina night.

3.0

20:39:13. Shit. There have been only four 36 hour finishers in the history of the Uwharrie 100 miler who went over the 20:30:00 timestamp to start loop 4 and only one person who went over 21:00:00- Nathan Maxwell, you have my respect. John’s and my chances to successfully finish the Uwharrie 100 were now somewhere between Buster Douglas knocking out Mike Tyson and the #16 seed defeating the #1 seed in the first round of the NCAA March Madness Tournament. In other words, it was not looking good. The metaphorical fat lady was warming up her vocal cords with “L” and “J” sounds. I looked so physically broken-down that a couple of aid station helpers kept telling me “Congratulations, Lou.” They thought I was a 100k runner and had just finished – because there’s no way a guy who looks like that is going out for 2 more loops.

John was in even worse shape than me. He had exhausted every marching cadence in the history of the US Navy to propel his surgically unhealed body to the 100k mark. His left knee was ravaged from 60+ miles through mountainous terrain, and at this point in the race, he qualified as wounded prey for the DNF vultures circling overhead. The new, new plan was to finish another 10 miles ourselves and save Pat for the back half of the 4th loop. However, if we came in after 29 hours to start the 5th loop, the race was over.

As John and I slothfully trekked through our 4th loop, I was absolutely certain that the angelic Uwharrie race directors – Dan and Amanda Paige – had “broken bad” and moved the Crossroads Aid Station back another 5 miles. That 6-mile stretch didn’t just feel long, it was eternal. We finally entered the Crossroads Aid Station and looked like two wayward Oregon Trail hikers whose oxen failed to ford the river. It was time to regroup in our respective sanctuaries. I went to the Port-A-Potty; John went to the food table. When I emerged, the Uwharrie 100 race would never be the same.

4.0

If you’ve followed the story thus far, you’ve likely deduced that John’s and my training for the Uwharrie 100 was at best, decidedly unconventional and at worst, haphazardly reckless. A reasonable reader, such as yourself, is justified to question why two people would handicap themselves with such a shortened (me) or non-existent (John) training cycle for a 100-mile race through the Uwharrie National Forest. John’s reason was clear-cut: his left knee was operated on over the summer and he was staring down a three month recovery to walk again. It’s easy not to log miles when you can’t stand on your leg. My reason, however, ties directly back to why I run 100-mile races in the first place.

Is there ever an ideal time to sign up for a race? Take a moment. Sure, you could convince yourself that pushing the race back “when you have more time” is a safer bet. Maybe you feel that you need to “buildup more mileage” or god forbid, complete a half marathon first. Author’s Note: If you have a 13.2 sticker on your car, I forbid you from reading any further.

If you’ve run a 100 miler before or are considering doing one in the future, humor me and walk in front of a mirror. Look yourself dead in the eyes and ask: “What is my “why” for running 100 miles?” Just to say, “I did it”? That’s not enough for me. Is it to increase the status of your social media page with a melodramatic post that you’ll start writing in your head on the last loop? That may be worse than the 13.2 sticker. For me – and the reason didn’t become clear until after this race – I want to know that I have gears in my body and Brain that I never knew existed. No one else needs to know that but me.

As you read this, what do you believe your physical limitations are? Maybe you think that you were born with Ford Pinto-esque machinery and restricted to a 4-speed manual transmission. Or maybe you liken yourself to a Mustang with a 5.0-liter V8. You’re both wrong. Your body is a spaceship with an infinite number of settings. The very idea that there is something buried deep within me that is greater than I could ever imagine is so fucking beautiful that I’m willing to risk everything in its pursuit. The problem is finding it.

Your Brain does not make it easy for you. If only uncovering your untapped abilities was as simple as a video game cheat code, where, after a series of simple button presses, you could unlock “invincibility mode.” Not quite. In my experience, you need to push well beyond what you thought was possible to prove to your skeptical Brain that you have more to give. It’s why watching motivational videos but never putting yourself in “The Arena” has likely done nothing for you. The Brain is too smart for that crap- it needs to be proven wrong internally, not externally.

Signing up for a 100-mile race only gives you the opportunity to discover the hidden aspects of your potential. Finishing a 100-mile race doesn’t guarantee you’ll learn anything about yourself. This is a sad irony that is especially true for the extremely prepared runner whose Brain “expects” its body to finish. The prepared runner faces a significantly more formidable challenge than the untrained runner because the former must push even harder to completely empty his tank...and still choose to bury his foot on the throttle thereafter.

Not training or barely training for a race of the Uwharrie 100’s magnitude all but guarantees you will be face to face with what lurks beyond your preconceived limitations. After all, your Brain’s logic is telling you that you have almost no chance. That’s when I know my trap is set. While my Brain is preoccupied with the improbability of my success, my Heart knows that I will never quit. I’ve never quit anything in my life and neither has my brother. In pitting our Hearts against our Brains, John and I manifested an internal Godzilla vs King Kong battle - admittedly, this is not an intelligent way to run a race. Nevertheless, I knew all of the inevitable collateral damage was worth the process of unearthing new strata within ourselves.

But we were going to have a hell of a time making the 29 hour cutoff first.

5.0

“Lou, there’s someone who wants to pace us.”

I must have heard my brother wrong. At mile 67, a box turtle with a bib number could have set our pace. I couldn’t imagine another human being willing to sign up for an eight hour crawlfest to mile 80 and the inevitable DNF John and I were headed toward.

“John, who are you talking about?” I looked around in the darkness and didn’t see anybody.

“Him.” John pointed to a diminutive silhouette that barely reached his mid torso. I couldn’t make this person out. I stepped closer. The silhouette grew smaller. Finally, a 5’5 Asian man stepped out of the shadows and a blinding beam of light shot out from the ground to the moon above. It appeared to encapsulate his entire body. I couldn’t tell if this person was about to be abducted or if this was his first descent to Earth. Scottish bagpipes played in the background while he spoke.

“My name is Tin. My runner withdrew from the race and I’m looking for someone to pace.”

We locked eyes for a moment and without saying another word, this man was clearly familiar with the Ultramarathon Hell that John and I now inhabited. Tin possessed the steely gaze of someone who had already swam through the coagulated, bloody waters of multiple 100-mile journeys through Hades and lived to talk about it. If John and I were willing, Tin was more than eager to navigate us out of this hell hole.

“Just look at my feet.”

“Roger that, Tin.” John and I were no longer part of a two-man democracy. We now fell under the command of our (mostly) benevolent Asian dictator/extraterrestrial, Tin.

“Just look at my feet.”

And then Tin took off. I don’t mean “took off” relative to the pace we were running. I mean this guy hurled his body into the night at a 9:00 min/mile pace. I opened my stride up. John was clearly in pain but matched me stride for stride. Two cripples at mile 67 kept on Tin’s ass like he just stole our wallets. The most perplexing part of this unexpected sprint was that my body felt strangely...good. I couldn’t focus on my right knee pain anymore because I was engrossed by Tin’s maniacal 180+ cadence. I felt like my brain fused with Tin’s feet and I was merely controlling my body from the outside looking in. This was the first – but not final - blow to my skeptical Brain’s perception of what I was capable of doing in this race.

We reached Sasquatch Summit in record time and then scaled it like we were Jon Snow and the Wildlings. As Tin and I reached flatter terrain and started to run, I noticed John was trailing behind. I went back to speak with him and assess the damage.

“John, what’s going on?”

“My left knee is fucked.”

My brother’s surgically repaired limbs had enough of the Uwharrie 100. Like a car that just had 4 tires stolen and was about to burst into flames, John’s lower body was cooked. I knew John didn’t want to hear it, but the fact he made it 70 miles already demanded a scientific study be conducted on how that was possible.

“John, stay on me. We need to keep pushing.”

I ran back to Tin. We started jogging lightly for a few minutes and I looked back. John was using a tree branch as a makeshift pole to keep moving forward. Damn. This was the decision I dreaded ever since Tin resuscitated our race. The math was clear: to finish the race in under 36 hours, I needed to leave John behind. Tin was providing a lifeline for only one of us to claim the buckle and leave the Uwharrie 100 victorious. But it’s not that easy. John’s my youngest brother. Almost three years ago, he stayed with me for all 29 hours and 30 minutes of the C&O Canal 100. After my first deployment in 2018, I wanted to do a 100-miler on 0.0 miles of training, and John was the only reason that I finished that race. Of course, I knew John would never want to hold me back or vice versa. I also knew that if we didn’t make the cutoff, we were coming back again next year.

I thought about it some more. Fuck it. I’m claiming the buckle from this race, and I’m going to saw it in half to give to him. There’s no way I would have made it to mile 70, to Tin, without John. The buckle belongs to John as much as it belongs to me. I ran back to John. He knew what was coming.

“John, I’m running ahead.”

“Go.”

I can’t fathom what it was like for Aristodemus – who the narrator in the movie “300” is based on- to be ordered by Leonidas to leave the battlefield of Thermopylae. Hell, who even knows what took place in 480 BC. What I can tell you is that when I left John - for dead - I could sympathize with the feeling of emptiness and obligation that Aristodemus might have felt. On one hand, I felt the void of having to earn the Uwharrie 100 buckle without John. On the other, I had an obligation to tell the story of a Warrior who faced insurmountable odds and was determined to go out on his Shield. Yes, I understand that we were not battling for the future of Western democracy; it was just a race, right? Well, if by the end of this story you still think the Uwharrie 100 was “just a race”, then I haven’t done my job at all.

I picked up my pace. John’s image drifted into the fog of the night as I ran hellbent on completing the Uwharrie 100 in under 36 hours. Give me the buckle and a saw. We aren’t coming back.

6.0

Night turned to day as Tin and I steamrolled to the halfway point of loop 4. As I ran up to “Boogie’s Bar & Grill”, Pat greeted me and was fully prepared to pace John and I for another 10 miles. Pat looked behind me.

“Where’s John?”

“Pat, change of plans. John is at least one hour behind me. Have food on you, bring a warm jacket for him, and walk John back here. It’s not about the race anymore, you’re on a search and rescue mission now.”

Pat nodded his head and took off.

My newly appointed authoritarian leader, Comrade Tin, graciously granted me two minutes to grab food and then get my ass back on the trail. I stepped forward out of the relative safety of the aid station and was immediately reminded that my adrenaline surge from the night prior was gone. I felt a searing, knife-carving pain in my right knee that could only be explained as my patella giving birth. I needed both a pacer and a midwife to get through the steeper downhills. Still, I knew that I was on the backend of loop 4 and making the 29 hour cutoff was within the realm of possibility.

“Just follow my feet.”

I wanted to say, “Tin, I’ve been moving for the past 26 hours, I have at least 10 hours left, and I’m tired of staring at your baby feet.”

What came out was, “YES SIR.”

Tin showed no expression and still had not broken a sweat yet. My initial hypothesis of him being an escaped Westworld robot or E.T. was still in play. I knew that failure to comply with Tin’s commands was not an option – it would have been the death knell of my race. Like it or not, Tin was the umbilical cord that connected me to the Uwharrie 100 buckle. Regrettably, that cord was also wrapped precariously around my neck.

Through a rhythm of hobbling, walking, and delicately picking up my right leg with one arm and placing it on the ground, I whittled out another 10 miles and ended the 4th loop saga. True to form, Herr Tin gave me 1 minute to get my shit together and was chomping at my heels within 30 seconds.

I was now in “CODE BLUE” territory of the pre-race plan and John’s grim prophecy was in its final act. How final? I wasn’t sure yet. As I wearily stood up from the orgasmic comfort of a half-broken camp chair, I closed my eyes and braced myself for the 20 miles to come.

I had about 7 hours and 40 minutes until the clock struck 36 hours. Naturally, it was not a lot of time given my physical state. I was sure my right knee was blown out, and I began to feel the presence of the same DNF vultures that circled John in loop 3. Now, I was the one who used a tree branch as a makeshift crutch and gently tiptoed downhill. Tin was patient, but I knew he was silently frustrated. We were bleeding time and still had the most difficult parts of the course to contend with.

I stumbled to the cursed Crossroads Aid Station for the 5th time. Tin asked what I needed. An uber. An orthopedic surgeon. Drugs. Lots of drugs. I was already at baby hippo levels of ibuprofen but needed enough pain killers to take down an elephant. As I gulped down another pill, a volunteer said something that almost permanently lodged the tiny, white capsule in my throat.

“Hey man, your brother made the 29 hour cutoff by 1 minute.”

My sleep deprived brain considered the math for a moment. My mind raced back and forth between the last images of John- he was buried in the wilderness like Dicaprio’s character in the “The Revenant”, as far as I was concerned. I sent Pat on a rescue mission, for god sakes. Could John have...no, no, there’s no way...it was physically impossible. A cycle of self-denial and incredulity ensued until I realized that I didn’t have time to debate with myself anymore.

My brother was still out there. Inexplicably, he was still in the race. I threw my tree branch crutch to the ground and straightened up. Tin, time to move out. Show me your damned feet.

7.0

While I moved like a salted slug to the next checkpoint, I had ample time to consider the gravity of John’s situation. He started loop 5 at 28:55:39. Remember when we discussed negative splits? John would essentially have to repeat his second loop time of 6:52:21 on loop 5 to make the final cutoff. For those of you who have run the Uwharrie 100, digest that for a moment. If this was a round in “Squid Game”, and you had to reproduce your second loop time on loop 5 to live, everyone would die. Oh, and by the way, we both still had to make the 33-hour cutoff at mile 93.7 (Boogie’s Bar & Grill).

I haven’t mentioned the 33-hour cutoff until this point in the story because truthfully, I considered it a formality if I was able to start loop 5. How hard could it be? In reality, Sasquatch Summit and Soul Crusher Mountain stood between me and Boogie’s Bar & Grill like a five mile stretch of quicksand. My right knee was a ravaged ball of inflammation and indistinguishable in size from my quadriceps muscle. I was walking more, stopping more, and unable to reduce my pain with Vitamin I.

Thankfully, my digestive system was still online. An iron cauldron of reliability, my stomach had endured over 85+ Gu gels in the past 30 hours to support my 700 kcal/hour requirement. There’s a reason you don’t see many – if any – 200+ lber’s at the ultra-finish line. In the midst of my suffering, I made a silent promise to write the Gu CEO after the race and thank him for creating the abhorrent, head-scratching “salted caramel” Gu flavor. No matter how much pain I was in, after one hit of a Salted Caramel Gu, I knew it could always be worse. Thanks for putting things in perspective, Gu R&D.

As predicted, time became dangerously scarce after I slugged my way to the other side of Soul Crusher Mountain. Tin was my nurse/motivator/pacer and talked me through each hazardous step like a point man through a Vietnam minefield. My new problem was that I was losing my grasp on the world in front of me. I didn’t feel tired per se, but I couldn’t trust the feedback my eyes were receiving. I saw dancing rock formations, talking trees, and people from my past who were playing hide and go seek along the trail. Suffice to say, I didn’t believe my eyes when I saw my other brother, Anthony, 50 yards in front of me.

Anthony, who owns two restaurants in the Triangle area, drove 2 hours to the Uwharrie trailhead because he heard that both of his brothers were at death’s door and in danger of not finishing the race. He already worked a morning shift at one of his restaurants and was due to work a full shift in the evening. To review, that’s 4 hours of total driving to see us for, maybe, 1 hour and then go back to work for another 10 hours. If you’re ever unsure of how someone feels about you, watch what that person does when helping you is inconvenient for them. Forget any grandiose promises – words are just distractions - and objectively look at their actions. With that in mind, it’s time to talk about my crew.

It was inconvenient for my sister to fly from Austin, Texas for 2 days and spend it sleepless while ensuring John and I had everything we needed during the race. But she did it. It was inconvenient for my Mom – who has attended every Ultra I’ve ever done – to blow her weekend (and the proceeding week) taking care of her man-children. But she did it. It was inconvenient for our friend Alex, who finished the Uwharrie 100 with a time of 32:38:35, to wait at the finish line without knowing if or when John and I would make it there. But he did it. It was inconvenient for my friend Pat to pace John and I throughout the race and for his girlfriend, Lauren, to come and hang out (with phenomenal sandwiches) until the race was over. But they did it. In fact, it was more than inconvenient for Pat: his restaurant shift wasn’t covered on Sunday (the second day of the race) and originally, he wouldn’t be able to stay out there with us. So, he did what any irrational friend would do and paid someone $200 to work his shift. This was the commitment level of the people in our corner; it was a Big Fish-esque ensemble who would do anything to see two people they cared about succeed - no matter how unlikely that was. And at hour 32:40, it was damn unlikely.

8.0

Once I locked eyes with my brother Anthony – and determined he was real – I did my best to smile and look better than I felt. Unfortunately, my gas tank was empty miles ago, and I couldn’t camouflage the physical destruction that my body had endured over the past 32+ hours. My brother noticed my weakened state and (as any brother should) pounced on it immediately.

“Lou, you look like shit.”

Thanks, Ant.

In between hurling poignant barbs, Anthony kept me engaged with stories of John’s miraculous 4th loop. Apparently, once John made the 29-hour cutoff, he was instantly surrounded by a village of aid station good-doers who were ready to help in any way possible. What a sight that must have been; it reemphasized how the ultra-community at the Uwharrie 100 was in a league of its own. Of course, this level of support wasn’t surprising given the attention to detail and enthusiasm of the race directors, Dan and Amanda Paige. Every time John and I brought up the rear at an aid station, Dan and Amanda were encouraging us to get back on the trail like we were in first place. Their genuine enthusiasm to “want” to give out a golden buckle gave us even more incentive to do right by them and finish the race in under 36 hours. It also made my state of suspended animation at mile 92.5 that much more depressing.

Anthony and Tin did their damnedest to sherpa me to Boogies Bar & Grill for the final time hack. My watch read 32:45:00 and the Uwharrie 100 Hourglass was leaking sand like a course sieve. In a new development, my hallucinations started to resemble Maximus’ visions of the afterlife in the movie Gladiator. Sadly, in my version, there wasn’t a beautiful woman waiting for me on the other side. Instead, I saw John screaming out to the Uwharrie Mountain Gods and running heavy footed behind me. I craned my neck just to make sure he wasn’t on my tail and then cursed myself for such a ridiculous thought. There’s no way John was close to me; I had at least 45 minutes on him. He might have started the 5th loop but John was going through the motions at this point. Or so I thought.

At 32:50, I saw Boogies Bar & Grill and was hit with the bittersweet realization that I was going to make the final cutoff but needed a breakneck aid station turnaround. Tin agreed.

“2 minutes, Louis. Not a second more.”

“Roger that, Supreme Leader Tin.”

I had a moment to reflect on the race so far:

Tin hurried me out of the aid station and I was suddenly thrust into the deep end of the Uwharrie’s final 10 miles. I knew that I could roll myself five miles downhill to the next aid station but shuttered at the thought of running the final five miles in 2 hours. By any measure, I stopped “running” a long time ago and was at peace with the inevitable surgery on my decimated right knee. Finishing under 36 hours wasn’t even important to me anymore; I made the 33 hour cutoff and I was going to move to the finish point if it took me two more days.

As the time neared 32:58, I looked around to see if John was approaching Boogie’s Bar & Grill. Despite my previous visions, John was nowhere to be found and it was obvious that his 100-mile journey was over. John made a valiant effort, no doubt, but his mangled left leg sealed his race in a concrete coffin that was already buried 6 feet underground. See you on the other side, bro.

I trudged downhill to the Crossroads Aid Station while my right knee mounted its final boycott against any forward progress. I was moving slower than a one-legged pirate with a walker and still had another 5 miles to go. Tin exhausted every motivational trick and legal form of verbal torture imaginable to propel me forward. Nothing helped. I one-two stepped another mile at a glacial 40 min/mile pace and started to write my Uwharrie 100 obituary.

My next words to Tin were, “I’m sorry.” I was letting down Tin, the supernatural being who selflessly jumpstarted my race at (what was then) my lowest point. Although Tin’s positivity never wavered, his frequent wristwatch checks belied his faith in my ability to make the 36 hour cutoff. My cantaloupe-sized right knee was another checkmark in the “No Way In Hell Are You Finishing This Race in under 36 hours” column. I daintily crossed streams like a blind, 3-legged baby deer. I started singing “Show Me the Way to Go Home” – the timeless sea ballad in “Jaws” – in Captain Quint’s register. I was Rose in “Titanic” and the Uwharrie 100 buckle was slipping from my grasp faster than Jack’s hypothermic body. Adios, goodbye. Nice knowing you. The fat lady of Uwharrie was done warming up. Sing it, girl.

“LOOOOOOUUUUUUU”

“TURN AROUND, IT’S JOHN”

The fat lady sounded a lot of like Tin. Wait, it was Tin. He was looking directly behind me with the same look I had when I saw Tin for the first time. Tin’s face became human all of a sudden: it showed emotion. He stared in the distance, slack jawed and in awe of an alien lifeform that took the human shape of my brother John. I didn’t turn around. I figured that I must have heard wrong. Or slipped and hit my head on a rock in the creek; surely, I would wake up from this “Gladiator” afterlife scene soon enough. And then I heard the sound.

Do you remember the first time you held your breath underwater and listened to your pounding heartbeat? Your mind is racing, thinking that you’re going to drown and the pulsing, deafening sound of your heart is urging you with every beat to dart to the surface. BOOM. BOOM. BOOM. That was the sound I heard. Whether the sound was internal or external, it didn’t matter. I had to look behind me.

There he was. Although it wasn’t quite John. What used to be John was now a rampaging, half human Clydesdale with glowing, pupilless eyes. It was like John had just been released from his horse carriage and was now running for his freedom. In front of John was his Tin, Kent, a pacer who joined him at the start of loop 5. I was in such a state of disbelief that I thought Dan dropped John off closer to me to bring my race back to life. I was in “code blue” status - hospital terminology for a cardiac arrest - and needed a fully charged electrical shock to have any hope of finishing this race in under 36 hours. I staggered forward as John closed the distance. He whispered something directly behind me.

“We’re going to finish this race like we’ve done every time before. Wait for me at the end.”

That was all I needed to hear. Like a city that lights up after a prolonged blackout, my adrenal glands came back online. I began to walk a little bit faster as epinephrine coursed through my veins from head to toe. I touched my right knee and didn’t feel anything. I was completely numb. My body was going through a spontaneous transformation that was more miraculous than a “just healed” grandmother in a shameless Televangelist commercial. I started to jog. I still felt no pain, so I started to run. And I mean, run. Like a “Forrest Gump breaking out of his leg braces” type of run. Before I knew it, I was on Tin’s ass and he strained to keep up with my new pace.

Tin was worried for me. “Save it”, he said. I don’t blame him; Tin was trying to look out for my race, but he didn’t understand what John triggered inside of me. How could he? Truthfully, the only way to understand that moment is to stop reading right now and find Pavarotti’s 2006 Olympic performance of the song, “Nessun Dorma.” John put Pavarotti squarely on my right shoulder and the Italian opera legend roared every bone chilling note in my ear. The final proclamation of Nessun Dorma is “Vincerò”– I will win. In a matter of a word, the Uwharrie 100 buckle was a forgone conclusion.

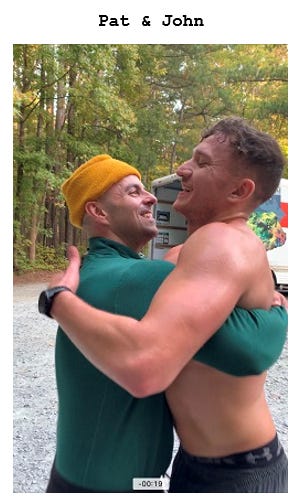

My final act of the race was to remove my shirt and pierce my bib number to my chest. I was sending a message to myself and anyone who knew me that my Heart held total dominion over my Brain. Nothing about how I ran this race was smart – why start now? I crossed the finish line at 35:50:02 and gave Tin a big hug. John and Kent were only 30 seconds behind me. It wasn’t until Dan handed John the inimitable Uwharrie 100 gold buckle that I realized John wasn’t dropped off by Dan to help me – he actually finished the damn race.

You’re astute to pose the question: So, John really made the 33 hour cutoff? I already told you that I never saw John near the aid station at the 32:58:00 mark. I never saw him because John never made the 33 hour cutoff. He entered Boogie’s Bar & Grill at 33:20:00. In Dan Paige’s infinite wisdom, the Uwharrie 100’s rules were bent to give John the opportunity to defy history; no runner had ever finished the course in under 36 hours after missing the 33 hour cutoff.

Remember what pace John had to run the 5th loop in to make the 36 hour cutoff? He essentially had to duplicate his 2nd loop time of 6 hours and 52 minutes (6:52). John ran a 6:54. Most astonishingly, he ran the last 5 miles in 1 hour and 26 minutes. 1 hour and 26 minutes between the Crossroads Aid Station and the Start/Finish point was the fastest anyone ran that segment all day and was only off Matthew Estes’ (the course record holder) time by 7 minutes. Unquestionably, John and I are indebted to Dan Paige for making such a visionary call. Dan’s willingness to see the bigger picture laid fertile ground for one of the most impossible human achievements I’ve had the fortune of bearing witness to.

In hindsight, the likelihood of my brother catching up to me in the Uwharrie 100 is not done justice by the word “impossible.” Seeing John at Mile 99 was an out of body experience that combined mathematical improbability with the realization of the Hero’s journey he – as a flesh and blood human – undertook to defy those odds. It’s the type of impossible where you try to convince yourself what is happening in front of your eyes isn’t actually happening. The type of impossible in “The Sixth Sense” where you can’t accept Bruce Willis was a ghost the whole time. It’s the type of story that I wouldn’t believe unless I was actually there.

Having been there, I think people misinterpret the Uwharrie 100’s slogan, “Simply Unrelenting.” It’s not the mountains or 100 miles that are simply unrelenting. “Simply Unrelenting” is the prerequisite character trait that you must possess to successfully complete this race. This is true if you are in first place or last. Especially if you are in last. My hope is that these chapters encourage you, Dear Reader, to stay until the end of the next race you run or crew at. As the race nears the final Golden Minute, you are guaranteed to find a compelling story. Those back-of-the-packers who barely survive a DNF are not sponsored ultra-athletes, probably have shitty ultrasignup ratings and won’t take home special awards like the Speedy Spider. But they are Lionhearts. And I bet they have a cautionary tale to tell.